Some years ago, when I was living in Belgium, my parents came to visit, and we drove over to England to see a cousin who lived here. (Well, we crossed the Channel by hovercraft, but you know what I mean.)

I don’t remember where we ended up going sightseeing, but I remember very well where we didn’t go: to the little village of Cerne Abbas, in Dorset, to see the Cerne Abbas Giant. My cousin diplomatically vetoed that as inappropriate for the conservative sensibilities of the party there assembled; you can see why from the photos.

The naked and decidedly male Cerne Abbas Giant is one of many, many displays known as hill figures or chalk figures in the UK, but one of only three—the others being the Uffington White Horse and the Long Man of Wilmington—that are thought to date from ancient times. Nobody knows who made them or why, but made they were, by cutting through the green turf and down to the white chalk beneath, and filling up, with more chalk, the troughs that were cut. (You knew southern England is built on lots of chalk, right? Chalk is what puts the white in the White Cliffs of Dover.)

I finally saw the Giant last week, though he looked a little the worse for wear. His head was pretty much gone, for starters, at least when looking with the naked eye—nakedness being something of the point of the priapic Giant. Lots of the interior details—the lines that you might see as ribs or as a six-pack; the pectorals and nipples—that makes this figure different from most others, which are plain, seem to have disappeared, too, along with his left arm and a good bit of the club he holds in his right hand. What he had instead, when I visited, was a somewhat polka-dotted (UK: spotted) midriff, with sheep as the polka-dots.

It takes a lot of work to keep the grass from growing back over the white outlines of a hill figure; it turns out that one good way of keeping the plants in check is to allow sheep to graze the hillside. (Not cattle; their hooves would mar the lines, apparently.) But sheep don’t have the ability—nor yet the tools—to do the job entirely by themselves. The National Trust, in charge of the maintainance, says it costs £1 per metre to re-furbish the white lines, which are about a foot wide (or 0.3 metre, if you prefer not to mix your measurements). As the Giant is the largest hill figure in these islands at 55 metres (180 feet) tall and 51 metres wide, and carries a club 37 metres long, that’s a lot of metres of outline to keep up, and it looks like it’s been a while since the Giant has had an overhaul.

The Giant as I found him, lines fading, and dotted with sheep, who are clearly no respecters of persons

During WWII, the Giant was covered over on purpose, to prevent German planes from using him as a landmark. More recently, he’s been used to advertise a variety of products, including condoms and, in 2007, The Simpsons Movie. For that, a comparably scaled (but non-aroused) Homer Simpson, in underpants and waving a doughnut, appeared on the hill next to the Giant. Funny, but…unfortunate. Let the Giant have his gravitas. (Homer was rendered in water-soluble paint, and washed away in the next rain, so that’s okay.)

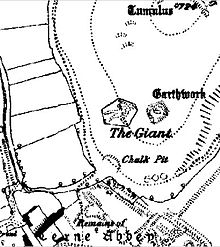

Another man-made feature, known locally as the Trendle, sits over the Giant’s left shoulder. That’s a rather odd name for a rectangular geoglyph (design on the ground) since trendle comes from earlier terms meaning round or circle or wheel. The Trendle is also called the Frying Pan (again, a round name for a square figure); the Giant is also called the Old Man, or the Rude Man (or so say internet sources; I’ve never heard anybody use those names); and the hill itself is call Giant Hill or Trendle Hill.

And while we’re on place names, what about Cerne Abbas? Cerne may be related to words meaning a circle, or a cairn (a pile of stones), while Abbas indicates an abbot. And in fact a nearby abbey, complete with abbot, flourished there until Henry VIII rousted out all the monasteries and took their lands and money in the 16th century.

It’s not clear why the monks and their abbot allowed such a pagan symbol to dominate the skyline—and maybe they didn’t. Some people claim the Giant isn’t as old as all that, and the lack of criticism from the abbey is part of their evidence. The first solid written record—which describes money spent on the never-ending task of clearing the weeds from the white lines—seems to date from the 17th century, whereas writers in the middle ages mention the White Horse of Uffington; the late appearance of written records, too, might suggest that the Giant didn’t appear much before the records did.

There are some—particularly since more lines, now obscured, seem to indicate the Giant used to carry a cloak or skin over his left arm—who say the figure is a traditional Roman depiction of Hercules, which would make him about 2000 years old, but then again, there are those who think some 17th-century servants cut out the Giant to criticize the way the landowner ran his estate. I can’t imagine how servants had the time or the energy to organize such a protest, or how they thought it would help their situation, but that’s no more strange than the theory that somebody cut the figure to insult Oliver Cromwell (who helped overthrow the monarchy for a while in the 1600s) or that the monks themselves did it, to irritate the abbot. Okay, this was before television and paperback books, but I thought the monks filled their long quiet evenings with prayer and/or flagellation, and besides—any monks, servants, or Royalists who started work on the figure would surely have been caught before they finished it; all the powers that be would have had to do was wait for them to come back. (The Trendle, in any case, is an Iron Age construction, probably a fortification.)

A local legend says that a real giant was killed on that very hillside, and people cut an outline in the turf around his body, which would make Giant Hill the first crime scene to sport a chalk outline of the victim. (Textbooks for modern detectives point out that such chalk outlines are seldom required, but also admit that every force seems to have at least one “chalk fairy” who can’t resist drawing them.) Many local people have, rather than speculate, accepted the Giant as a fertility symbol, whether they believed a woman who slept on the hill would conceive soon afterward, or that having sex on the giant assured fertility, or that dancing around a maypole in the Trendle assured fertility, or…there are probably infinite variations. Some said a woman who walked around the figure three times would ensure that her lover was true; I’d say your lover could get up to a lot of mischief while you were hiking around and around. In any case, every May Day, a troupe of Morris Men still dance in the Trendle and in the streets of Cerne Abbas to ensure good crops.

So I finally made the acquaintance of the most prominent citizen of Cerne Abbas. Long may he ensure the fertility of the beautiful Dorset countryside.