(British readers will probably find the headline for this post trite, a cliche; American readers probably won’t know why. Read on to find out.)

You think Christmas is long gone? There’s one Christmas tradition in Britain that begins in earliest November, and in some places runs well past the end of January, without anybody complaining that it starts too early or stays too long. And it’s almost invariably known by a diminutive of its proper name without anybody—not even me—complaining that people shorten the name. And that’s panto.

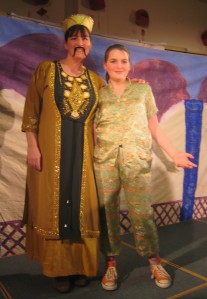

The Genie of the Ring (Alison Moulden) and the Genie of the Lamp (Andy Wells) at a neighbourhood production of Aladdin this season

Yes, it’s short for pantomime, but there’re no coyly silent mimes grinning from under berets; panto is louder than most theatre performances, because the audience gets to talk back. A lot. It’s not panto without audience participation.

A panto is ostensibly a play for children, although I’ve read that well over 90% of people in Britain see a panto every year, a total which must include people who, like me, have no children to give them an excuse. They dramatize a few traditional children’s stories (generally Cinderella, Snow White, Babes in the Wood, Puss in Boots, Sleeping Beauty, Dick Whittington, or Aladdin), but it’s common to see whole families showing up with three or even four generations. In the best pantos—well, in my opinion—a lot of the lines work on two levels: straightforward and wholesome for the kiddies, with a second and ever-so-slightly racy sense for adults.

Good vs. Evil stories sink or swim on their bad guys, and this production lucked into a wonderful villain, the sorcerer Abenazer, as played by Lara Milne, with enormous swishing cape and truly evil chuckle. In another of those British-English spelling variations for words ending in -er, Abenazer appeared in the programme for this production as “Abanaza”. (In the edition of the Arabian Nights I have, he’s only called “the African magician”, and has no name.)

All pantos offer dastardly villains, whom we are encouraged to boo. Each stars a principal boy: a plucky young male hero played by a beautiful young lady. Each includes a pantomime Dame: an older female character (or two, in the case of Cinderella’s evil stepsisters), played by an older man. Assorted members of the company handle the parts that complete the story, as well as the musical numbers, slapstick sketches and other wacky mayhem the director has dreamed up. The most fun I’ve had in years came when some of these players of unnamed parts—in this case, the Lost Boys and the “redskins” (ah, yes; we’ll come to them in a minute) of Peter Pan—handed out grey, foam-rubber, cube-shaped “rocks” to the crowd. (Sorry, I don’t know the British term for foam rubber, although I do know it isn’t foam rubber.) They told us to wait for a particular line, and then defend Peter Pan from Captain Hook by throwing our rocks. Our cue came in the second act. The air filled with flying grey blocks. We threw ours from the ground-floor seats, got pelted with rocks that didn’t make it to the stage from the audience in the balcony, picked those up and threw them at the stage, too, while the pirates on stage picked up all the rocks they could and threw ’em back; it was total bedlam, and complete second-childhood bliss, all to the music of the 1812 Overture.

Ahem.

In calmer productions, the cast may throw candy into the crowd, or ask you to check your seat to see whether there’s a golden key hidden under it, or just ask for volunteers to come on stage to help with some of the nonsense. Inevitably, there will be traditional lines for the audience, a sort of call-and-response that all British-born people seem to know, apparently having absorbed it with their mother’s milk.

The hero, you see, depends on the audience for messages about some of the action. Often it’s that the villain is creeping up, which the audience indicates by shouting out together “He’s beHIIIIND you!”, to which the usual response is “What?” so that the audience can shout the line again and again, only louder. Granted, this makes the characters seem a bit dim; they also seem rather contrary, going by the traditional disagreements, which go something like this:

Dame, as Evil Stepsister: “The glass slipper is MINE!”

Audience: “Oh, no, it isn’t!”

Dame: “Oh, yes, it is!”

Audience: “Oh, no, it isn’t!”

Dame: “Oh, yes…”

(Repeat until the last moment before it gets tiresome; timing is everything.)

Widow Twankey (Rosemary Woodcock) and the Emperor of China (Jo Heaphy). Rosemary gets special credit for stepping into the role when the gent who was playing the Dame had to cancel; she did the cast proud, at one point turning a line she did remember–“I don’t know what to do”–into a hilarious cry for help–“I don’t know what to do. I’ve no idea what to do [to crew offstage] Tell me what to do!“

Then there are audience lines I just don’t get, which nobody has been able to explain, most notably “Oompah, oompah, stick it up your jumper”. Even if you take into account that oompah and jumper rhyme (well, sort of) in standard British English, it’s still nonsense. But much of panto is nonsense.

Sometimes, though, it’s politically incorrect nonsense. Peter Pan includes a tribe of “redskins” that I would venture to say would not be seen on any American stage today, certainly not under the name redskins. And then there’s Aladdin, which is set in China. China?

As a child, I thought Aladdin lived just down the road from Ali Baba, in a land of camels and date palms—but listeners the world over like tales of exotic lands, and apparently the original Arabian folktale set Aladdin in China. That China, however, is a land where shops close on Friday to observe the Muslim holy day, and the inhabitants are called by names such as Mustapha (according to my edition of the Arabian Nights). The panto version sticks to the original as far as setting the scene in China—but not much beyond that.

In the world of panto, Aladdin’s Chinese mother conforms to English stereotype by running a laundry, which seems a bit culturally insensitive, but…okay; there must be laundries in China and somebody has to run them, presumably somebody Chinese, as it’s doubtful there’s a long-running cultural exchange program whereby English people run laundries in Beijing. Aladdin’s brother, a laundry worker, is called Wishee Washee (hmmmm…) and their mother is called Widow Twankey—a name that comes from the supposedly Chinese brand-name of a low-grade tea once sold in Britain, chosen to hint that she’s past her prime, since that tea consisted of old leaves. But then we come to the Emperor’s guards, a trio of Keystone-style cops—Woo, Choo, and Poo—who’re played as fools, and who swap their Rs for Ls. They appear several times, “rooking for Araddin”, and talk about practicing karate, a Japanese art, as if Asian cultures were interchangeable. With their entrance, the play descends so far into stereotype that in the US it would be frankly offensive, but it’s cheerfully accepted here as just good fun.

The Emperor and Wishee Washee, played by mother-and-daughter team Jo and Amy Heaphy. I loved the orange hightops!

We wondered, at our neighborhood production of Aladdin this year, what the family sitting next to us, clearly from some far-eastern country and very possibly Chinese, would think. To go by their reaction, Asian immigrants don’t mind. And the girls playing the Emperor’s Keystone-like guards were, just like the girls playing Aladdin, Wishee Washee, and Rosebud (equivalent of Disney’s Princess Jasmin), so beautiful, they just glowed—despite enormous false moustaches, in the case of the guards. You couldn’t help but cheer them.

This Aladdin, performed for friends, parents, and locals in a church hall, was a blast, every bit as much fun as a professional panto with big-budget bells and whistles. Nobody minded when the villain, still in character, dropped suddenly off the script, following a silence after “Noooow, Aladdin…”, with “Noooow, Aladdin, I have forgotten my line”. Somebody offstage helped, and the whole effect was so charming, it seemed inspired. They ought to write such things into the scripts on purpose.

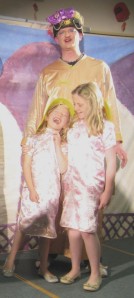

The Genie of the Lamp (Andy Wells) with two members of the chorus: Emily Moulden (left) and Ellie Wells (right), daughter of the Genie himself

For all I know, they have. It’s traditional to change lines in the script, to add bad jokes (“My dog can talk! How’re you feeling?” “Ruff!” “What’s that on the tree?” “Bark!”) or to namecheck local places and personalities. Characters in the local Aladdin went up the Farnham Road from Onslow Village, and saw the Hog’s Back—all local features, neither Chinese nor Arabian. It all adds to the wacky (UK-ians might say “daft”) humour of panto that gives us a Wishee Washee in orange hightops, a Chinese/Arabian chorus singing Michael Jackson, and a Genie of the Ring who keeps a can of beer (UK: tin of lager) under her turban and whose theme song, played at her every entrance, is Nokia’s default ring-tone—get it? Get it?)

All over Britain, churches, amateur dramatics societies, and community groups put on local pantos at Christmas-time, while for professional actors, pantos are big business. Sir Ian McKellan took time off from being Gandalf a while back to play Widow Twankey; John Barrowman (of Doctor Who and Torchwood) defied tradition to take the part of Aladdin (in a production visited by Daleks) several years in a row; and a famous soap star (Steve McFadden of Eastenders) reportedly earned £200,000 (about US$300,000) as Captain Hook in a production about 5 miles from my house. You can find them in the National Database of Pantomime Performance along with the smaller fry, and you’ll see there that some of these larger productions actually continue into March.

No, really–March. So, do you think Christmas is over? Oh, n— Well, now you know what to say.