When is the Supreme Court not the Supreme Court? When sitting as the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council (JCPC). This post on the JCPC wraps up the series sparked by my recent visit to the Supreme Court building in London.

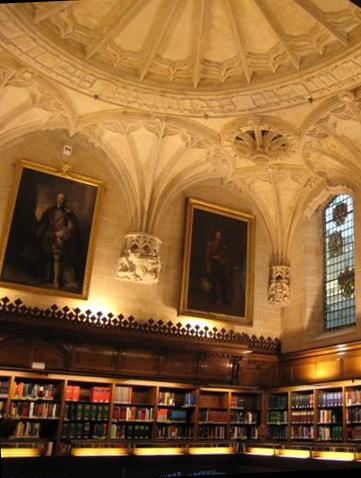

Court 3 in the Supreme Court building, where the Justices hear JCPC cases. When in use, the little flags--just there to give visitors an idea of the countries which bring cases here--are removed, and a full-sized flag from the country whose case is to be discussed hangs from a full-sized flagpole.

The USA’s judicial system is a streamlined modern marvel compared to Britain’s—unsurprisingly, since the American version was planned and instituted so recently, something over 200 years ago. The British system has evolved over at least ten centuries, accruing bits as the world modernized and the British empire grew, dropping bits as the colonies became independent, obliged to take into account all kinds of ancient rights and privileges. The upshot is that the Crown-in-Council—that is, the monarch, aided by advisers called the Privy Council, which was the ultimate appellate court for the Empire—has been left with the final word on cases from a surprising mishmash of jurisdictions, including some in foreign countries.

Today’s Privy Council has 600 members, and all of those who are judges are technically on the Judicial Committee, the body that hears Queen-in-Council cases. In practice it’s almost always Supreme Court Justices who sit as the JCPC in Court 3 of the building (the first two courtrooms are described here). These come from some deliciously named lesser-known courts, the most archaic-sounding being the Court of Admiralty of the Cinque Ports, which deals only with naval law as administered along a certain stretch of the south coast. And the JCPC hears appeals from other military courts, such as those in Sovereign Base Areas, though there are only two of those left, and they’re on Cyprus. Then there are prize courts, for cases concerning ships or other spoils seized legally (ahem) in wartime; I don’t know when such a court last convened, much less referred a case to the Queen-in-Council, but it must have been a while ago.

A few ecclesiastical courts can still send cases: the Church Commissioners, who handle investments and real estate of the Church of England; and the Chancery Court and the Arches Court, which handle disciplinary matters among English clergy. The Chancery Court of York covers the northernmost third of the country; the Arches Court of Canterbury in reality covers the rest although theoretically it has authority over only the Archbishop of Canterbury’s London peculiar—a peculiar being an area not subject to the bishop of its local diocese. (This particular peculiar consists of 13 parishes in London.)

I can’t imagine cases come up often; I’ve just included all of this because I thought that bit about the peculiar was so wonderfully…peculiar. The bulk of the JCPC’s caseload comes from Crown Dependencies, British Overseas Territories, and former colonies.

Each Crown Dependency has a different legal relationship to the Crown, but in general they recognize the Queen’s authority and depend upon her for defense and such, but they are not part of the United Kingdom. The best-known are the Isle of Man and the Bailiwicks (a bailiwick being the jurisdiction of a bailiff) of Jersey and Guernsey, two little clutches of islands off the coast of France. It remains to be seen whether anyone will take seriously the 2008 claim by the (putative) owner of Forewick Holm that this Shetland island, which he’s renamed Forvik Island, is a Crown Dependency and therefore not subject to laws passed by Parliament.

And here's another door, an interior one, leading to... the coffee shop. This has to be the most elegant coffee shop entrance in London. I peeked in at first, unsure whether I was really allowed to open it. Odd that the only place I felt might be off-limits, and wasn't sure I was welcome, was the coffee shop; that just points up how open and welcoming the Supreme Court is about its work.

British Overseas Territories range from the British Antarctic, inhabited only by researchers, to the British Indian Ocean Area, the world’s largest marine reserve. (It has no civilian inhabitants except fish, because the UK evicted all the civilians for military reasons, alas.) There are twelve other British Overseas Territories, all of them small islands: Pitcairn, Montserrat, and so on.

And then there are several independent countries that find it useful to appeal cases to the JCPC rather than to fund and run their own ultimate appeals courts. On any given day, the JCPC may hear cases from Jamaica (in the Caribbean), the Falklands (off the tip of South America), Mauritius (off Reunion Island, which is off of Madagascar, which is off of Mozambique, in case you need reminding), or Kiribati (32 South Pacific atolls plus one honest-to-goodness island, which I’m tempted to say are in the middle of nowhere except that they are really quite close to the intersection of the International Date Line and the equator, which is—in cartographical terms, anyway—probably the antithesis of nowhere).

It may no longer be valid to say that the sun never sets on the British Empire, but at one time—presumably when India and Canada participated—one quarter of the world could appeal cases to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council. Even drafting in senior judges from the countries involved to help, Justices still had to grapple with legal niceties of (here I can’t do better than quote from the JCPC’s website):

- Roman Dutch law from South Africa, British Guyana and Salome

- Spanish law from Trinidad

- pre-revolutionary French law from Quebec

- the Napoleonic code from Mauritius

- old Sardinian law from Malta

- Venetian law from the Ionian islands

- medieval Norman [French] law from the Channel Islands

- acts of the Oirwachtas from the Irish Free States

- Muslim, Buddhist and Hindu law from India

- Ottoman law from Turkey, Cyprus and Egypt

- Chinese law from British courts in Shanghai

- tribal law from Africa

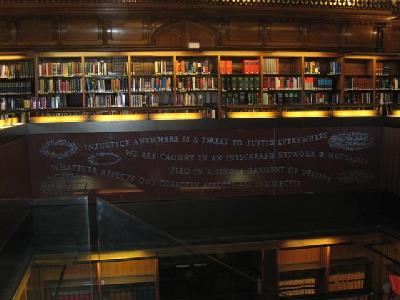

This is the lawyer's suite, where lawyers can confer and prepare. The room seats over 30 lawyers who are in the building for cases at either the JCPC or the Supreme Court, and sometimes there are that many involved in a single case.

Though some countries listed have now withdrawn from the British system, that’s also not a complete catalog. It leaves off Brunei, for example, even though the JCPC hears cases for the Sultan from time to time as a courtesy, reporting back to him rather than reporting, as is usual for the Privy Council, to the Queen.

Lastly, in one more improbable legacy of history, appealed cases from the Disciplinary Committee of the Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons go to the JCPC. (There must be a good story—possibly a shaggy dog story—of how that came about.)

All of these can have their cases heard in Court 3 by right. The Committee cannot refuse such appellants; unlike the Supreme Court, the JCPC doesn’t get to chose which cases are worth tackling, and there are a lot of cases to get through. Almost half the cases the Justices of the Supreme Court heard last year were JCPC cases from other countries.

In another strange twist, even though Britain doesn’t have the death penalty, the JCPC rules on points of law which can mean life or death for appellants from countries that do. In one of the last cases to come from Belize, the Justices decided that a judge there had acted unlawfully in the way he applied the death penalty, and as a result a condemned man’s sentence was converted to life in prison.

There are fewer countries participating all the time; Belize withdrew from the system last year, and before that New Zealand left in 2004. But even without them, and even without obstinate priests and obstreperous soldiers, dubious veterinarians and debatable spoils of war, it’s unlikely that the Justices will be idle. Even though the British like to accuse the US of being excessively litigious, plenty of British people do turn up in court. I reckon there’ll be enough homegrown cases to keep the Justices in business for a few more centuries.